HafenCity: A MODEL CITY ON THE WATERFRONT

TEXT: STUART FORSTER

Photo: Unsplash

“Europe’s largest inner-city urban development area is a blueprint for the new European city on the waterfront,” says André Stark, the press spokesperson for the HafenCity in Hamburg.

The district encompasses 127 hectares of former dockland and disused space on Grasbrook, an island in the River Elbe. The HafenCity information centre lies just over a kilometre’s walk from Hamburg’s grand city hall. Visitors can learn about the ambitious project’s scope inside of the characterful brickwork building that once housed the powerplant that provided energy for the neo-gothic warehouses of the Speicherstadt district – which UNESCO designated a World Heritage Site in 2015.

“A lively new city is taking shape,” explains André, noting that spaces for work and residential purposes stand within close proximity. Retail and educational premises are also present. So too are points of interest relating to leisure, culture and tourism.

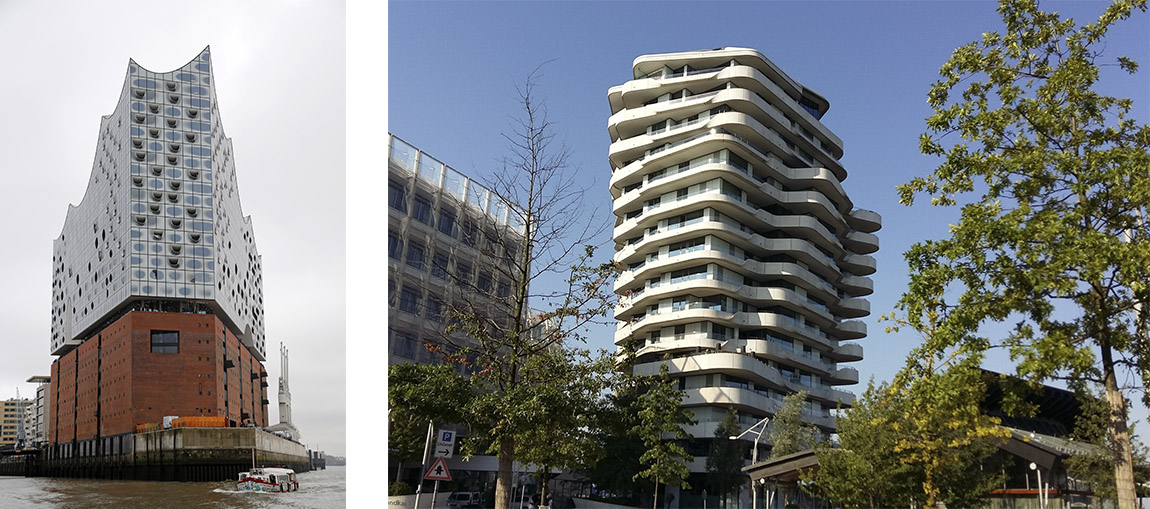

Notably, the Elbphilharmonie, Hamburg’s mixed-use waterfront icon rises over the Elbe from the HafenCity. It features concert halls, private residences, is the location of the upscale Westin Hamburg hotel and hosts a popular viewing platform – known as The Plaza – offering vistas of the city and its port.

Considerations regarding both environmental and economic sustainability underpinned HafenCity’s innovative design. They range from the choice of building materials to the design of public spaces including parks, squares and promenades. The area is notable for its social diversity and mixing. A sustainable heating supply and smart mobility concept are also key aspects of the development.

Historically, Hamburg has suffered more than most European cities because of extreme weather conditions. In February 1962, thousands of buildings were destroyed, leaving approximately 60,000 people without a home, and more than 300 residents killed as a result of Der Sturmflut. The natural disaster is known in English as the North Sea Flood.

Access to the sea, 110 kilometres away, remains both a fundamental aspect of Hamburg’s economic wellbeing and a part of the port city’s character and soul.

“The intensive interaction between land and water is unique,” says André. “Despite the risk of occasional flooding, HafenCity is neither surrounded by dykes nor cut off from the water. With the exception of the quays and promenades, the whole area is being raised to between eight and nine metres above sea level. The concept of building on artificial compacted mounds, known as warfts, lends an area once dominated by port and industrial uses a new topography – retaining access to the water and the typical port atmosphere while guaranteeing protection from floods.”

The Stuttgart-based company Behnisch Architekten designed the waterfront New Work Harbour building – office space formerly occupied by Unilever. The angular building embraces innovative technology to attain sustainability and provides workspace and meeting rooms for more than 900 employees of New Work SE, the parent company of Xing. Rather than utilising a traditional energy source to cool the building, thermally activated concrete exploits lower temperatures below ground. Additionally, a film around the façade shields automated blinds that help regulate the temperature indoors.

Speicherstadt. Photo: Stuart Forster

“It is not only urban development and infrastructure that contribute to the sustainability of HafenCity, but also each individual building. The financial amount of approximately ten billion euros invested by developers alone, as opposed to approximately three billion euros spent by the public sector, demonstrates the crucial importance of the properties being built in terms of the ecological quality of the district and also its social and cultural quality,” explains André.

An advance purchasing strategy meant that most of the land in the HafenCity was owned by the city prior to development commencing. From the outset, the objectives included redefining international standards for conceptual and architectural quality. One way of striving for consensus regarding what would be good for the city as a whole was by discussing ideas in the broadly representative Commission for Urban Development.

That brought advantages, as André points out: “It has been possible to use the allocation of land to developers as a central control mechanism via the process for awarding planning options and concept tenders. This approach provides, among other things, for high architectural quality in HafenCity, street-level space for retail and cultural uses, diversified housing offerings with price differentiation, communal areas and neighbourhood management.”

Ultimately, new thinking and infrastructure are urgently needed to meet environmental challenges, including protecting biodiversity and stopping global warming. That means adopting both a sustainable economy and adapting lifestyles.

“The development of cities is of particular importance in this context, as 77 per cent of the population living in Germany is concentrated in conurbations. Since a large part of our cities has already been built and the existing stock can only adapt gradually, the importance of neighbourhoods that are at the planning stage or under construction is that much higher,” observes HafenCity’s press spokesperson.

“Because the development of HafenCity simultaneously creates an institutional framework for integrating new model projects, it provides a highly regarded platform for innovation,” concludes André as to how forward-thinking Hamburg is playing a pioneering role in developing a climate-friendly urban zone that aims to foster social progress.

Left: Elbphilharmonie. Photo: Stuart Forster. Right: Marco Polo Tower. Photo: Pixabay

Subscribe to Our Newsletter

Receive our monthly newsletter by email